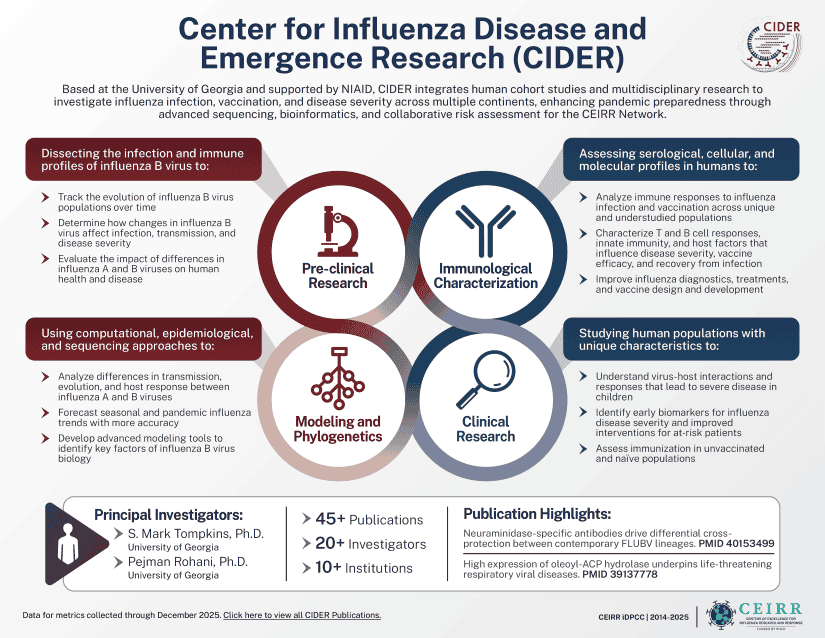

Composed of seven multidisciplinary and collaborative Centers, the CEIRR Network aims to understand the natural history, transmission, and pathogenesis of influenza, and provide an international research infrastructure to address respiratory viral outbreaks. One such Center, the Center for Influenza Disease and Emergence Research (CIDER), seeks to “understand the natural history of influenza viruses to explain why influenza viruses emerge and cause severe disease, as well as predict virus emergence, trajectory, and impact.” Under the leadership of S. Mark Tompkins, Ph.D. and Pejman Rohani, Ph.D., both at the University of Georgia (UGA), CIDER’s research stands on four interconnected pillars:

- Pre-clinical Research

- Immunological Characterization

- Modeling and Phylogenetics

- Clinical Research

Collaboration and integration are central to CIDER’s approach to studying influenza and have been so even before its inception. Dr. Tompkins was part Emory-UGA CEIRS during the original CEIRS contract starting in 2007. In 2018, as Dr. Rohani was co-leading a project with Dr. Tompkins, they decided to explore developing their own Center under what is now known as CEIRR. They noticed that “there had been considerable and diverse growth in influenza-related expertise at UGA over the past decade,” so they leveraged this expertise in an independent proposal based at UGA. By 2019, Drs. Tompkins and Rohani assembled a team of national and international colleagues to complement UGA’s influenza expertise, bringing together novel human cohorts, experimentalists, and computational biologists. They secured “pre-seed funding” from UGA to advance this proposal, which led them to organize a one-day meeting with their collaborators in early 2020 to refine the CEIRR proposal. Over the next couple of months, Drs. Tompkins and Rohani compiled their collaborators’ research sections and wrote the core of the technical proposal, culminating in a “marathon weekend” to complete the successful proposal on March 2, 2020.

Today, CIDER’s 24 investigators have shared over 45 publications on influenza infection, vaccination, and disease severity across multiple continents. Their work has covered large-scale computational, epidemiological, and sequencing approaches to model influenza transmission, track evolution, and forecast seasonal and pandemic trends, as well as more detailed studies to dissect the infection and immune profiles of influenza B viruses. A special branch of CIDER’s research program includes studying influenza dynamics and immunity in human populations with unique characteristics, such as children who develop severe disease, at-risk patients, and unvaccinated and naïve populations. These studies assess the immune, cellular, and molecular profiles of populations who are infected with and/or vaccinated against influenza to characterize responses and improve influenza diagnostics, treatments, and vaccine design.

A recent discovery exploring the differential immunity elicited by the two lineages of influenza B virus, Victoria and Yamagata, from Dr. Tompkins’ laboratory greatly excited both leaders from CIDER. “Epidemiological studies and data from human cohorts suggested accelerated divergence of the flu B lineages and potentially distinct post-infection immunity.” When Dr. Tompkins’ team explored these phenomena with pre-clinical models, they found that “recent Victoria lineage viruses elicited immunity against subsequent Victoria and Yamagata infection, while Yamagata infection did not prevent subsequent Victoria infection.” Further, this immunity was partially mediated by neuraminidase-specific antibody responses. The leaders mention that this study “offers insights into possible contributors to the disappearance of the Yamagata lineage in 2020,” and emphasizes the importance of studying influenza B viruses, a particular area of interest for CIDER. To learn more, read the full publication.

Looking ahead, Drs. Tompkins’ and Rohani’s vision for the CEIRR Program includes “greater integration of empirical and computational science,” especially in a scientific landscape that stresses speed in responding to outbreaks of emerging viruses with pandemic potential. They also emphasize "high-risk, high-reward" research, meaning pushing the boundaries of difficult but innovative studies. They believe that a large, multi-investigator, multi-disciplinary program with long-term contracts (e.g., 7 years), much like the CEIRR Program’s infrastructure, is ideal to enable “high-risk, high-reward” research. By fostering these studies, CIDER hopes the CEIRR Program will continue to push the boundaries of influenza and respiratory pathogen research, ultimately enhancing pandemic preparedness and response capabilities.

The iDPCC interviewed Dr. Tompkins to learn more about his experiences:

1. Who/what inspired you to go into science in general?

A. Several of my parents and grandparents had careers in biomedical research and medicine. Their stories of their careers were exciting, and their jobs were interesting to me when I was young. In high school in Ontario, I had a biology teacher, Andrew Liptak, who was always excited about science. In class, he would do things like jump up on the bench and dance around to describe Brownian motion, and we would also discuss primary research like the work of Köhler and Milstein, wondering how these discoveries could impact science and the world. His passion, seasoned with a bit of crazy, convinced me to study science in college.

2. Do you have any hobbies or special interests that you'd like to share?

A. I really enjoy seeing live music and am actively trying to attend as many concerts as I can of all the classic rock bands and artists before they stop touring or die. The Canadian ProgRock trio, RUSH, is my favorite band, and I attended many of their concerts. Sadly, the drummer passed away from glioblastoma in 2020. The remaining members were clear that they would not tour as RUSH without Neil Peart. When that happened, it really energized me to seek out the artists I wanted to see and, if they were touring, attend a show.

3. Are you a morning person or a night person?

A. I am very much a morning person but occasionally enjoy being a night owl. On those occasions, I am less of a morning person, or I am a cranky morning person.